Creighton professor puts Willa Cather on a pedestal

One hundred years after winning a 1923 Pulitzer Prize for her novel, One of Ours, novelist Willa Cather took her place among the greats of Nebraska history in the National Statuary Hall Collection at the Capitol Building in Washington, D.C.

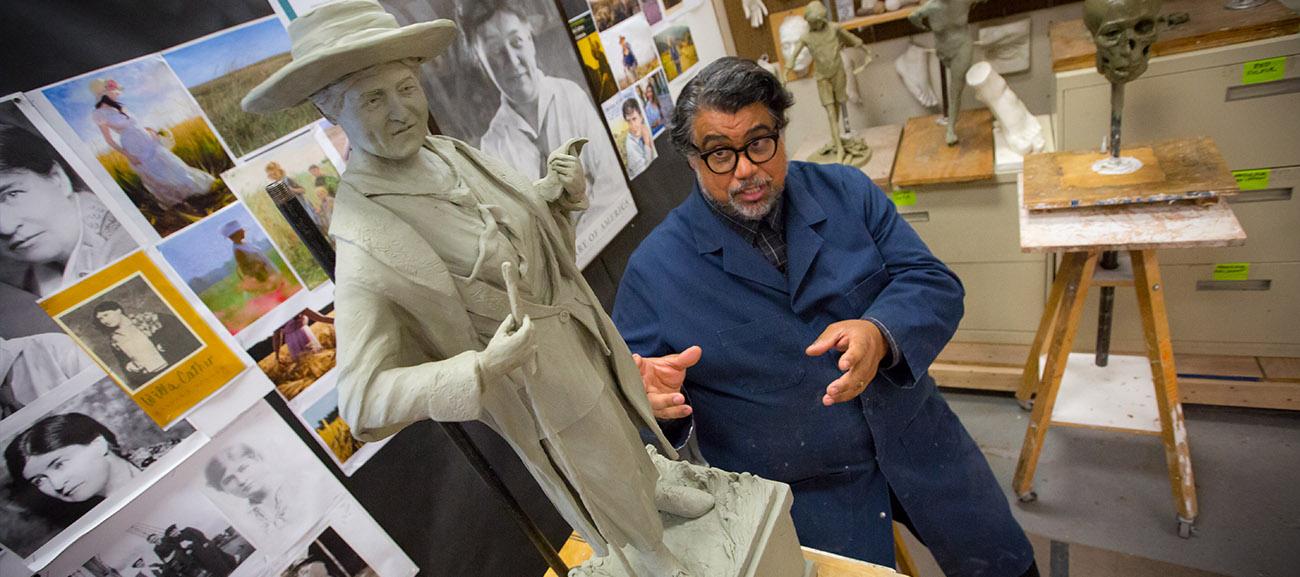

A seven-foot bronze statue, created by Littleton Alston, MFA, a sculptor and professor of fine arts at Creighton University, was installed on June 7, becoming one of 100 statues distributed throughout the U.S. Capitol Building, two from each state. Alston’s Willa Cather replaces a statue of Nebraska agriculturalist J. Sterling Morton, which has represented the state since 1937.

A statue of Chief Standing Bear became Nebraska’s second statue in 2019, replacing an image of U.S. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, a three-time Democratic Party nominee for president of the United States who had also represented Nebraska since 1937.

The Cather project was awarded to Alston after he was chosen from 70 competing artists across the nation.

“I was surprised and elated,” Alston said, when notified of his selection.

“I have to have a connection in some manner to enter a competition, and I had that with Willa Cather. I knew her writings, and I felt this was something I could do.”

The Cather statue, which will stand in the U.S Capitol Building for decades to come, reflects Alston’s sense of her as a storyteller.

It depicts the author striding through a field, wearing a broad-brimmed hat and her famous jacket with a western meadowlark, the Nebraska state bird, and goldenrod, the state flower, at her feet. Cradled in her left arm are pages from an ongoing work, and at her left foot a half-submerged wagon wheel. That wheel, Alston says, tells the story.

“That the wagon wheel is partially buried symbolizes not just progress, but also the lives lost during the journeys that brought people to Nebraska,” he says. “Along that path, there are graves. Graves of children, of mothers, of old people who could not get all the way across.”

Awareness of the human story that brought those people to a wilderness where they and their descendants built great cities tends to fade with the passage of time, Alston says.

“We tend to think of them as ‘pioneers,’” he says. “We don't think really of what they did, what it took for them to uproot and take their family — and maybe their piano — to literally put all their hopes into a new land.

“It symbolizes loss, it symbolizes memory, it symbolizes progress, it symbolizes the cycles of life and death, even within the land itself, and how you see the land. If you look at Cather’s writings, her early writings, she talks about peeking out of the edge of the wagon as a child and just seeing open space. That is the story.”

With the installation of his Willa Cather statue, Alston became both the first African American sculptor to have a statue displayed in the National Statuary Hall Collection and the first Nebraska sculptor to create a statue representing the state.

As professor of sculpture at Creighton, Alston is well known for creating realistic bronze sculptures of prominent figures, both life-size and busts, often with symbolic themes.

Among Alston’s many public works that can be seen around Omaha are sculptures of civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.; National Baseball Hall of Fame pitcher Bob Gibson; Pro Football Hall of Fame halfback and return specialist Gale Sayers; NASA astronaut Air Force Lt. Col. Michael Anderson, MS'90; Mildred D. Brown, civil rights activist and founder of Omaha’s historic black newspaper; and St. Ignatius of Loyola.