Getting real: The millennia-long quest for authenticity

It’s been a long time since Plato sat beneath a grove of trees holding forth on the authentic human goodness of Socrates, but the discussion of authenticity — what it is, what it means and how we should pursue it — has never slowed.

Aristotle, sitting at Plato’s feet, developed his own ideas until some 350 years later Christianity began stressing the importance to an authentic life of a contemplative, inner spirituality. And so the centuries passed, as various understandings of authenticity were advanced — all parts of a parade colored by names that echo through the history of Western thought: Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Heidegger, Sartre, de Beauvoir, Camus, to name but a few.

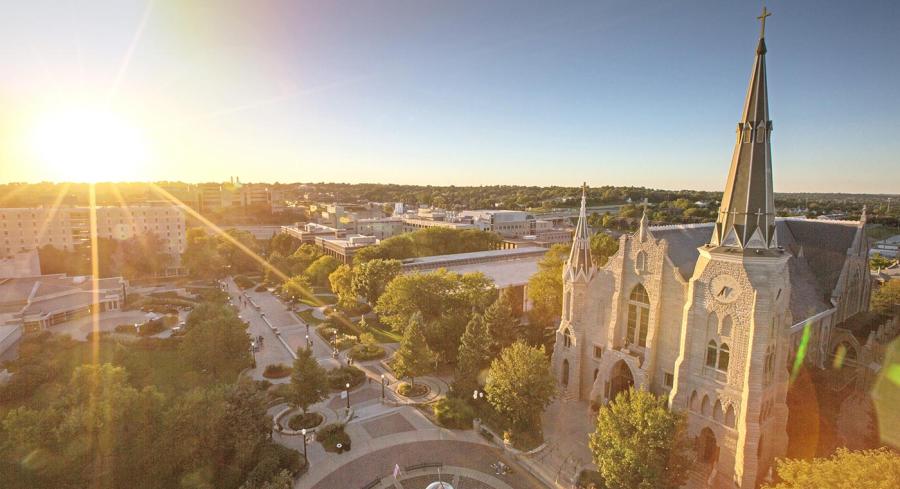

So, was anything resolved after all this contemplation? Do we at last have a decent grasp on what it means to live an authentic life? We decided to set sail across Creighton’s campus in search of an answer.

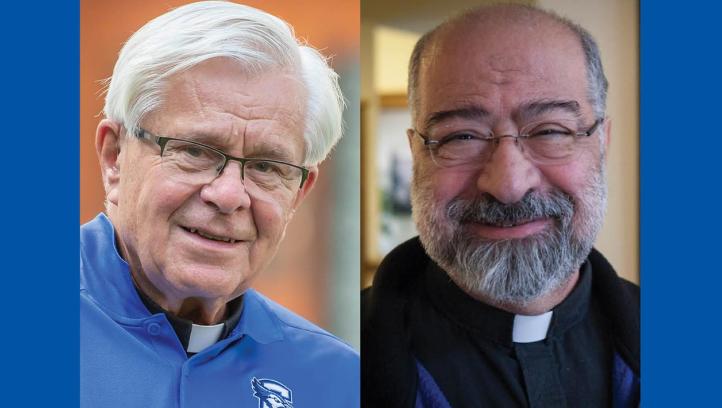

An important port of call, as is usually the case, was the office of the Rev. Larry Gillick, SJ.

Fr. Gillick, director of Creighton’s Deglman Center for Ignatian Spirituality, works in a modest though comfortable office atop a flight of stairs in one of the oldest buildings on campus, squeezed between St. John’s Church and Creighton Hall. Physically blind since a childhood accident, he has during his more than 40 years on campus built a reputation for spiritual insight.

So, we asked him the big question: What does it mean to be authentic?

A long silence ensued. Then, words — a stream of them, slowly enunciated.

“Let me talk about some words,” he says. “I'm going to talk about receptivity. Generosity. True humility. Awareness. Reflection. Dependency. Adventure. Mystery. And honesty.”

And so he does, his thoughts on those various qualities resolving eventually into a single admonition: Don’t hide.

“Hiding is inauthentic,” he says. “As is not being adventurous, not allowing mystery.”

People often think that God is a mystery, Fr. Gillick says, but this is not so. God is simple. God is One. People, on the other hand, many and diverse even within their individual beings, are the real mystery, and the discovery of who anybody authentically is requires a willingness to emerge from hiding and to embrace adventure.

“The authentic person allows mystery and darkness and invitation,” Fr. Gillick says. “Not hiding. The inauthentic person hides from being authentic. I hide because I want to be who you think I am, or what you think I ought to be able to do, and I don’t accept my limitations.

“I don’t want you to see them, and I don’t want me to see them. So, I will live only the life that has no experience of my limitations. It’s pretty island centered. I know all the trees on my little island, so there is no adventure, and I can hide. I might say, ‘I’m not hiding, I’m right here,’ but I’m not knowing myself. The authentic person experiences awareness, acceptance, donation.”

The authentic person, Fr. Gillick says, understands that he or she has purpose and is not afraid to discover what that purpose may be.

“The authentic person knows he or she is an agent of creation,” he says, “meaning that I allow you to create me, and I allow myself to be an agent of God’s creation of you. That is a central Jesuit thing. I’m open to your helping me know who I am. But the more I accept that, the more I am not mine — I become more for you. And if I am hiding, I am not going to be for you. If I am hiding, I cannot be a creational entity for you or an agent of God’s grace.”

Notebook entry: Don’t hide. Be open to adventure and to the unraveling of your personal mystery. Be open to the idea that others can help you discover who you are, even as you, as an agent of God’s grace, do the same for them. Authenticity is a voyage of discovery. Don’t be afraid to set sail.

So, we set sail. Our next port of call is the oldest campus building — Creighton Hall, the original college structure from 1877 where the ghosts of Creighton Past mingle with the students and administrators of Creighton Present. Here presides the Rev. Daniel S. Hendrickson, SJ, PhD, president of Creighton University, whose latest book, Jesuit Higher Education in a Secular Age: A Response to Charles Taylor and the Crisis of Fullness, we hope will have something to say about the journey toward authenticity.

We do not travel alone in our conversation. Having swapped his clerical collar for civilian garb, Fr. Hendrickson looks every bit the college professor whose doctorate in the philosophy of education allows him to welcome to the discussion such clashing existentialists as the 19th century Protestant philosopher Søren Kierkegaard and the 20th century atheist Jean Paul Sartre; and then, evidently his favorite — Canadian philosopher and social theorist Charles Taylor, who, at the age of 90, is still with us.

Fr. Hendrickson finds Taylor’s idea of “fullness” closely related to authenticity.

“For Charles Taylor, ‘fullness’ is about myriad relationships with ourselves and with others, and with God,” Fr. Hendrickson says. “The God part is the most important for him because it is the biggest aspect, but he thinks we are all connected, and I think he’s right.

“In my book, I speak about the three pedagogies of fullness in Jesuit higher education, the ways we teach and work with students to form more self-awareness, stronger relationships with others, solidarity with those who don’t live like we do, and then connect somehow to God.

“Those are my three pedagogies — the pedagogy of self and study, the pedagogy of solidarity or connecting with others, and the pedagogy of grace, which is openness to an experience beyond us.”

It is that pedagogy of grace — an openness to a higher power and to the mystery and the beauty of higher things — that Fr. Hendrickson says leads to an authentic human experience.

“Taylor says that Western secularism — which is the U.S., Canada, Scandinavia and Western Europe — is shutting down our ability to be in relationship with God, and therefore we are less authentic,” Fr. Hendrickson says.

“He says that we in the West need to be re-enchanted, even haunted, by the presence of God. He won’t say you should go to church and pray, because he’s an impractical philosopher in the sense that he doesn’t tell us what to do — which is true of all philosophers — but he does kind of want us to do that. He wants us to be in relationship with a higher power, or with a God. That, for him, is the best expression of fullness and human authenticity.”

Notebook entry: Exercise your unique human ability to perceive a beauty and a power beyond the mundane. Experience “fullness” by developing awareness, building relationships with others and embracing a relationship with a higher power.

Fr. Hendrickson suggests visiting with Patrick Murray, PhD, and David McPherson, PhD. Both are philosophy professors in the venerable Dowling Humanities Center, which is barely a stone’s throw from Creighton Hall. So, there we go.

Murray is splendidly rumpled, in the professorial way, having stashed the crisp suit he wore the previous day when receiving Creighton’s Kingfisher Award for contributions to the humanities. An internationally known authority on the theory and philosophy of Karl Marx, and the holder of Creighton’s John C. Kenefick Faculty Chair in the Humanities, Murray has taught philosophy for 51 years, more than 40 of them at Creighton.

He cheerfully rescues from a pile of papers and books copies of Martin Heidegger’s Being and Time and Søren Kierkegaard’s The Sickness Unto Death. There are many views about authenticity, Murray says, mostly addressed within the branch of philosophy known as existentialism, but given limitations of time and space we focus on Kierkegaard and Heidegger.

“Kierkegaard says that despair is sin,” Murray says. “So, what is despair? Despair is not wanting to be yourself. That is the short answer. That is inauthenticity. Authenticity is affirming yourself or being yourself.”

But who are we?

“For Kierkegaard,” Murray says, “the only real authenticity is as a Christian believer, because, he says, Christianity delivers the truth about who we are.

“Now, he railed against what we call Christendom — the institutional, official Christianity where you go to church because everybody goes to church because that’s the way it is done in a Christian country — but his idea is that authenticity is being yourself, and that to know what you are requires understanding what it means to be a human being.

“If you don’t have the right answer to what it means to be a human being, then you are condemned to inauthenticity.”

A turbulent relationship with Christianity and Catholicism led Heidegger to different conclusions, Murray says, to assertions that an authentic life requires being a social being and coming to grips with the world we inhabit. The key to such human growth is using foresight to gain an authentic perspective as we move toward the inevitability of death, Heidegger’s famous concept of “being-toward-death.”

Notebook entry: Do not despair. Affirm yourself. Understand what it means to be human. Embrace the world. Be a social being.

On to David McPherson, whose thoughts are given via the miracle of Zoom. He’s at home, apparently in a book-lined attic, but engaging and cheerful. An authentic life, he says, requires a lodestar, a goal, a purpose in life, something to work toward and aim for — otherwise the search for “authenticity” can lapse into just so much navel-gazing.

“Authenticity properly understood, and that which we should be concerned with promoting, involves a kind of looking inward to what we resonate with that is also looking outward to something of value beyond ourselves,” he says. “What is most important in human life? What goods should I orient my life toward?”

“I think it connects in certain ways with the Ignatian practice of discernment, of coming to discern what God’s will is for my life. For Ignatius, clearly, doing the will of God was his lodestar, but what it means to do God’s will, will be different for each individual.”

There are ways to consider the issue that need not employ the language of religion.

“Another way to think of it is, what is my calling?” McPherson says. “What is my vocation? Authenticity has an important role in that it asks us to look within ourselves to see what is most important. We must engage in that process of understanding.”

Crucially, he says, authenticity cannot be — as might be lightly assumed — doing whatever you feel like doing.

“That can lead to a really problematic situation where if we recognize no objective values, no objective goodness, then why care about anything?”

Notebook entry: Establish goals, internal and external, and be true to them. Resist destructive instincts, pursue things of value that lie beyond the self.

Discovering Personal Authenticity

The discovery of personal authenticity, an undercurrent of a Jesuit education, occurs quietly and almost invisibly as learning mounts and viewpoints evolve. Understanding and guiding that process falls to frontline educators, among whom are Colette O’Meara-McKinney, EdD’20, assistant professor of dentistry and associate dean for student affairs, and Corey Guenther, PhD, associate professor in Creighton’s Department of Psychological Science.

O’Meara-McKinney runs the Program for Ignatian Mindfulness at the School of Dentistry, which helps students develop resilience by applying Ignatian principles of gratitude and self-awareness.

She is very helpful — indeed, mindful — and has prepared notes in which she says authenticity is “the alignment of our words, thoughts, actions and emotions” and “being honest about what’s in my heart and in my head in a way that is respectful and compassionate.”

Her demeanor, as befits an associate dean of student affairs, is patient and warm.

“Sometimes, life is just challenging, and we’re sad or upset or frustrated or disappointed,” she says. “And all those emotions are real and legitimate. Sometimes, I have students in — and there’s a box of Kleenex here for a reason— because something has happened. It can be anything from, ‘I didn’t do well on a test’ to ‘I just broke up with my girlfriend.’”

People are at their most vulnerable at such moments, she says, but vulnerability is a big part of authenticity because it leads to honesty.

“I think if we are truly being our authentic selves there is an alignment with who we are, who we aspire to be, our emotions, our words — all those things are in sync. I don’t think you can be authentic if you don’t have some vulnerability,” she says.

“You are not trying to fit in, you are not going with the group, you are not answering in a way that you think will be well received, you are being honest. It is that alignment with personality, sense of self, values, priorities — when those things are aligned, I think it gets you through the good, the bad and the ugly still intact.”

Notebook entry: Don’t fear vulnerability. Embrace honesty. Develop gratitude.

Over at the Skutt Student Center, in the commons area down by the coffee shop, awaits Guenther. As it happens, he has studied “authenticity” and is eager to share what he and other researchers have found. Engaging, brimming with data and highly conversant with the latest psychological research into authenticity (which he says picked up serious speed in the mid 1990s), Guenther has some surprises.

“The research I have been doing recently gets into the question, what does it mean to be authentic, what does it mean to feel authentic,” he says. “It’s quite clear. We feel more authentic when we feel good about ourselves.

“Historically, we have thought about authenticity as being something that reflects genuinely accepting strengths and weaknesses, truly knowing yourself well, whereas a lot of recent research says that may not be the case.”

The fact is, Guenther says, that human beings are authentically biased toward thinking well of themselves, that their overall well-being improves when they focus on their good traits, and, conversely, can decline by dwelling on failings.

“We might say that we aspire to accuracy, that we want to truly know ourselves, but in practice we want to truly know our good selves,” he says.

While this challenges reigning assumptions that authenticity demands awareness of strengths and weaknesses and a clear-eyed assessment of “who we are,” the body of research, Guenther says, shows that a profoundly authentic trait among people, across cultures, is that they do better when they think well of themselves.

“In fact,” he says, “people who aren’t positively biased tend to exhibit symptoms of mild depression. Having slightly biased positive self-views predicts so many measures of mental well-being.

“What I am saying is probably contrary to most people’s definition of what authenticity is. But data suggest that authenticity for our species is not necessarily self-accuracy but that we thrive and do our best psychologically and even physically when we are slightly self-biased in a positive direction. That might be the right framework to construe authenticity.”

Notebook entry: Accentuate the positive, eliminate (or at least sideline) the negative. Your good self is your authentic self. Lift it up.