Study sees ‘partnership’ as essence of ‘culturally effective’ healthcare

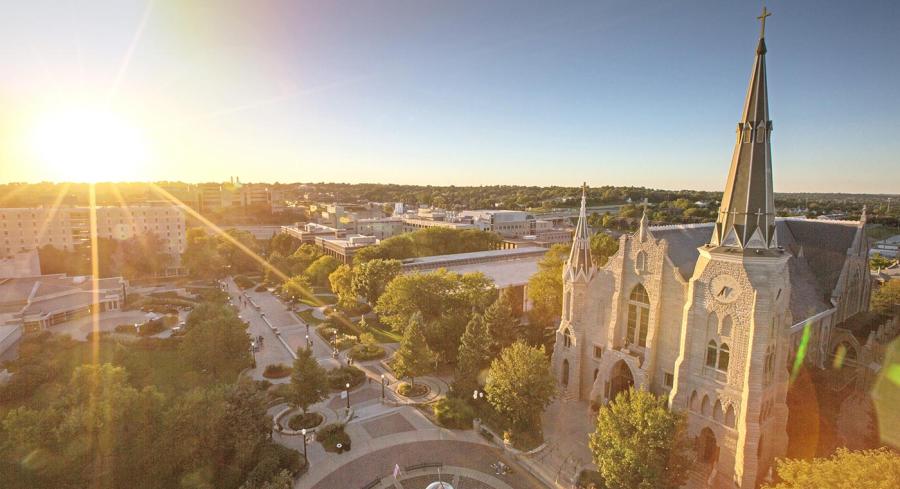

A groundbreaking research study to define, measure and elevate culturally effective care in rehabilitation services is underway at Creighton University’s School of Pharmacy and Health Professions.

Funded by a George F. and Susan Haddix Research Fund Award and led by Julia Shin, EdD, assistant professor of occupational therapy; Sarbinaz Bekmuratova, PhD, assistant professor of occupational therapy; and Jamie Nesbit, PT, DPT, assistant professor of physical therapy, the study solicits input directly from members of racial-ethnic minority communities in an effort to understand their experiences, needs and desires regarding how they wish healthcare providers to address culture.

Described as “culturally effective care” by Shin’s research team rather than the more traditional “cultural competency” framework, the approach stresses mutual partnership between the care recipient and the provider, inviting care recipients as experts in their own cultural backgrounds to enrich the care accessed and received.

This partnership balances the power differentials present in the healthcare experience, traditionally directed by the provider, so that both parties are open to new learning and understandings.

The prevailing approach to cultural competency in medical and health sciences education, which Shin experienced during her student days, includes educating the provider with examples of traditions and cultures of minority populations. But that, she warns, can prove troublesome.

“If the provider assumes that ‘I am culturally competent, and I know these four cultures,’ it can lead to stereotyping, overgeneralization and a closed-ended mindset that interferes with cultural humility and continued learning,” Shin says. “There is no way that I, or any other provider, can be an expert of every family’s culture – the care recipient-provider partnership, with continuous interaction and learning, is the key to cultural effectiveness.

“I have experienced the ironies first-hand,” she says, “and I felt burdened and guilty all the time, because I was trained to think that I should know how to provide culturally effective care — I was supposed to be a culturally competent occupational therapist. The truth is, I did not know how to invite my clients to be my partners – and teachers and masters of their culture.”

Her research team, which includes Tyler Wright, a physical therapy student, and Jordan Ortiz and Allison Tung, both occupational therapy students, has gathered information from three African American groups, one Korean-speaking Asian group, two Hispanic groups and an English-speaking Asian group. Recruited through flyers, support groups and racial-ethnic organizations, the participants explain during sessions lasting between 60 and 90 minutes what culturally effective care means to them.

“We asked them about any disparities they have experienced based on their racial-ethnic identities, and they were very candid about what that felt like and how they want to see providers meet their unique cultural needs,” Shin says.

“They definitely want to be listened to more, and to participate more in the decision-making processes. They don't want to be told what to do. They want really to partake in a partnership.”

That idea of “partnership” defines the concept of culturally effective care that the research team is building. It envisions teaching patients and their families how to advocate for themselves and how to develop the strategic and diplomatic skills that make it easier to express their cultural needs. The flip side, of course, is teaching providers to be open to meeting the expressed needs of their racial-minority clients.

“We are going to assume that clients can, as equally as providers, learn and acquire the knowledge, awareness and skillsets to be advocates of culturally effective care for themselves,” Shin says.

“Eventually, we want this partnership to be part of regular clinical practices where clinicians can create a safe space and empower families from racial-ethnic minority backgrounds to advocate for their cultural needs — just make it a part of everyday practices.