At the confluence of science and religion

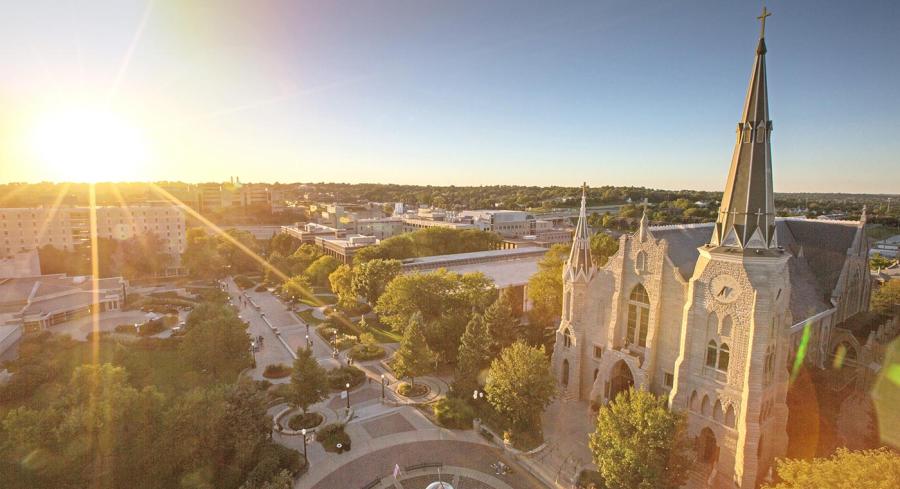

Exploring the intersections of science and faith was the focus of a two-day public conference hosted by Creighton in April at its Omaha campus, with an opening lecture at the Kiewit Luminarium, a new interactive science museum located along Omaha’s riverfront.

The conference featured faculty and student presentations and national speakers, including the Rev. Robert Spitzer, SJ, PhD, former president of Gonzaga University, who has written and spoken extensively on the intersection of science, reason and faith.

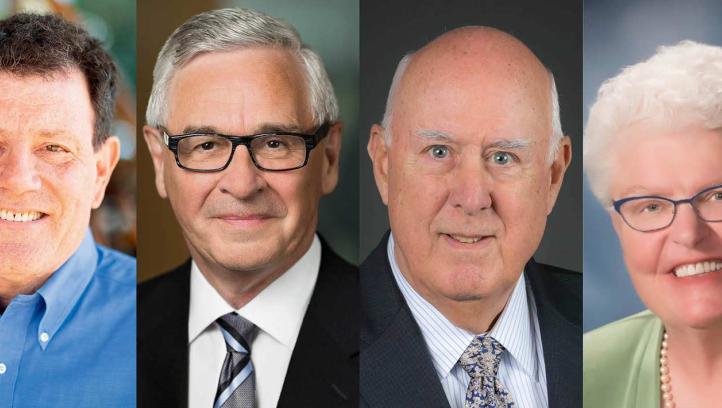

Prior to the event, Creighton magazine had an opportunity to talk with conference organizers Gintaras Duda, PhD, professor and chair of the Department of Physics, the Rev. Chris Krall, SJ, PhD, assistant professor of theology and neuroscience, and Tricia Ross, PhD, a scholar on the history of science and religion and an assistant professor in Modern Languages and Literatures and the Honors program.

Creighton Magazine: How did you get interested in this area of study, both personally and professionally?

Duda: My research area is theoretical particle physics and cosmology. I grew up looking at the sky and wondering. I also grew up Catholic, and in my research area we’re talking about those big questions. We’re talking about cosmology and the beginning of the universe. Those are scientific questions, but they are also spiritual, theological, philosophical questions. You’re looking at the world with blinders on if you’re only thinking about that scientifically or theologically.

Ross: It was kind of a roundabout route for me. This interplay [between science and religion] fascinated me, in part because it touched on questions I had since I was quite young. I grew up in very conservative Christian circles and, basically, I was scared of evolution. And I didn’t want to be scared. I found that through directly engaging it, thinking through it and tracing the relationship over a very long period of time, it helped. It was also just so fascinating.

Fr. Krall: My interest goes back to a bike ride my sophomore year of high school. There was something in the way the wind was going across the trees and the lake and then hitting me. It was like, how does this all fit together? What’s the music of the spheres, the harmony of existence? I came back from that bike ride, and I decided I was going to major in physics and philosophy in college. And I did. [After graduating from Boston College, joining the Jesuits, attending the University of Toronto’s Institute for the History & Philosophy of Science & Technology, and completing other studies], I went to the Ian Ramsey Centre for Science and Religion at Oxford University – where there was more conversation, more dialogue, more engagingness on this whole question. Then, I finally finished off with a PhD at Marquette University in neuroscience and theology. So, I’ve been studying this for a good while.

Creighton Magazine: How would you describe the relationship between faith and science. Do you see them as complementary or in conflict?

Fr. Krall: The term I use is dialectic. There is a tension, but not a tension in the negative sense. It’s like the tension of a trampoline that allows one to jump up and down. Or the tension of a violin string that allows for music to be created. There is certainly some conflict of sorts, but it’s helping us in discovering what the universe truly is – a bringing together of the physical and the metaphysical. In Catholic theology, we are incarnational beings. We are necessarily beings with physical and scientific realities, but pointing and drawing us to the one who creates the fullness of all – the way, the truth and the light.

Ross: I present it very similarly, not as conflict, or even necessarily as a complement, but as conversation. There are these two pursuits of truth – reasonable pursuits of truth – that come at it from different angles. But they are united in this whole common goal, which is for us to understand ourselves and the world in which we live in, and what is the meaning and purpose of it. An apparent conflict might come when there is something that we have not fully understood yet. We don’t always completely understand how the two relate. It can lead to intense, productive conversation.

Duda: I think people compartmentalize these two types of ideas. They have their religious beliefs and their scientific beliefs, and the two don’t talk to each other or interact or engage. And that’s really not the Catholic model. The Catholic model is that faith and reason are mutually complementary. Through dialogue, through intersection, through consideration of multiple lenses, we arrive at something we understand much better, much deeper, much more fully. And this is a richer understanding of reality. We look at the world in this much more profound way, and we see more rather than seeing less.

Fr. Krall: (Pope) John Paul II in his encyclical Fides et Ratio (1988) uses the image of two wings lifting us up into these higher realms of understanding.

Ross: But the relationship sort of shifts and moves. As we learn more of science, it changes. And our understanding of theology grows. I think the relative prioritization of science over faith, or spirituality or religion, has changed culturally. But I don’t know if that’s fundamentally about science and religion conflict, as just a cultural shift toward prioritizing science.

Fr. Krall: Reading Newton’s Principia, he can be viewed as a very religious person.

Ross: He is but that’s at the end. The whole book is dense physics, with no religion. But then at the end, he’s like, “But there are these other things that I can’t explain, so it must be God holding the spheres together.”

Duda: That’s part of a “God in the gaps” kind of thing.

Creighton Magazine: God in the gaps? What do you mean by that?

Duda: It’s a particular perspective that says that religion is the thing that people invoke when they don’t quite yet fully understand the science. We don’t understand how science works, so this must be God’s direct intervention in the world, or miracle, or something along those lines. Whereas, if we had understood the science well, we would have known this was just another example of a natural phenomenon. Given enough time, we’ll figure it out. It is extremely arrogant. We’ve been blessed by such a tremendous explosion in scientific technology in the last century, but we’re limited human beings. There’re limits to knowledge. We won’t be able to understand everything.

Ross: As science began to gain explanatory power with the scientific revolution – an era typically dated from around 1543, when Copernicus’ Revolution of the Heavenly Spheres came out, to 1689, when Newton’s Principia was published – people started thinking, “Oh, we can figure out everything. Science is going to explain everything.” There’s a struggle in that period. They’re struggling with what they’ve inherited. What can they keep and what should they throw away?

Duda: That’s a good segue to what we have today. We’re still struggling with that.

Ross: The idea of a fundamental conflict between science and religion that has endured throughout history is actually a product of the 19th century. Two vehemently anti-Catholic authors, John Draper and Andrew White, claimed that the Catholic church was suppressing science. The titles of their books (History of the Conflict Between Religion and Science, 1874, and A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom, 1896) include “conflict” or “warfare” between science and theology. People just kind of bought this fake history in the 19th century. And now it’s become part of the cultural consciousness. It’s a relatively recent historical narrative.

Creighton Magazine: So how can faith and science work together to enhance our understanding of the world?

Fr. Krall: I’m obviously biased, but when you look at the human person, there’s so much complementarity. The big questions like free will and human flourishing, the soul. When is the human person fully alive? Well, from a psychological, physiological, heart-rate variability, you can look at all the different things. But when you think about a soul, freedom and making choices, it’s all part of this integration. Finding meaning is the key. There’s meaning in a very physical sense but meaning itself also recognizes something more.

Creighton Magazine: Beyond evolution and the beginning of the universe, where else do we see this tension between faith and science play out?

Ross: I would also say bioethics. A lot of my students struggle with that, even more than evolution. It kind of surprised me. I kind of assumed everyone would have the same problem as I did, which was, “How do we deal with evolution?” Many students are more concerned about genetic engineering. What can you do? What can’t you do? What is the line? How do you determine that?

Fr. Krall: Because we can do it, should we?

Creighton Magazine: Do you find your students asking questions and wanting to explore more about the intersection of faith and science?

Duda: There’s a hunger out there for this kind of thing. This is something that we take seriously. In the Physics Department we talk about, why is there a physics department at a Catholic, Jesuit university? What is our purpose for being here? How should we be different?

Ross: I’ve been teaching a survey on the history science and religion every fall for the past five years. And students always tell me that it’s a question that they struggle with. And they’re glad to find some space to talk about it.

What I like about it is it shows you that you don’t have to be afraid of either science or faith. You don’t have to be afraid of it. It’s good to ask hard questions.