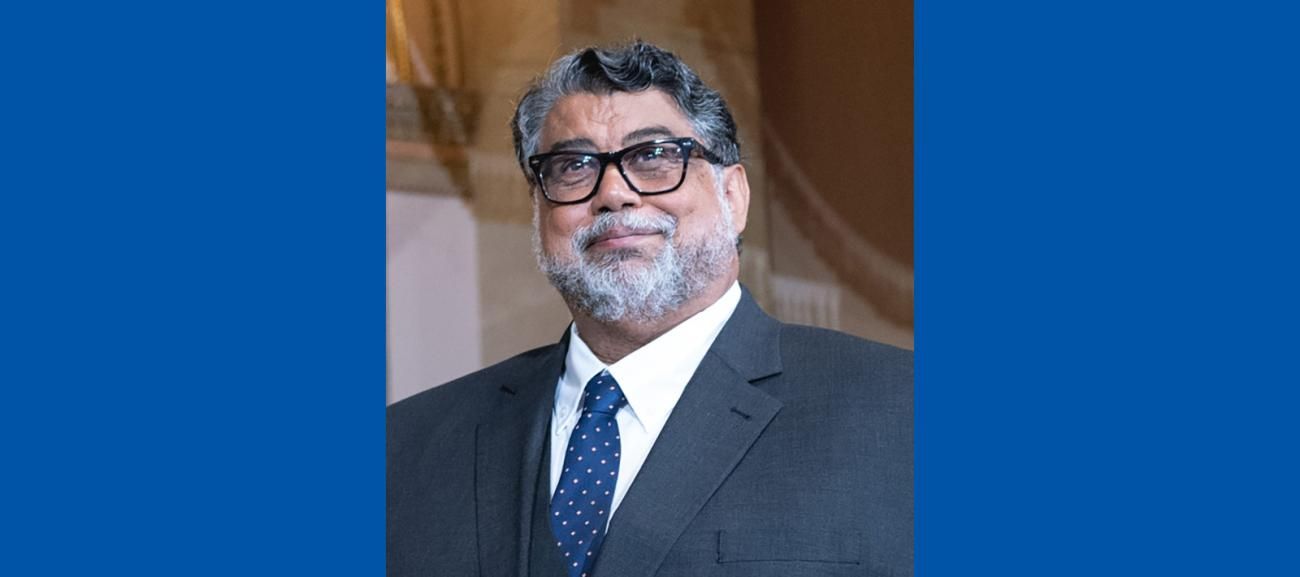

How Littleton Alston found his way to Statuary Hall

Littleton Alston, MFA, immortalized Willa Cather in June, cementing his reputation as a sculptor of renown, but the journey to that moment began long ago when a very different woman saw past the poverty of his childhood, past the trials of a Black kid growing up in Washington, DC, and past the angry uprisings that followed the 1968 assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

It took a teaspoon of hope and a cupful of faith, but Gilbertha Alston believed that in her son’s scattered drawings accumulating in the basement of their rickety house near Washington’s 14th and F streets there shined bright promise.

And that made all the difference.

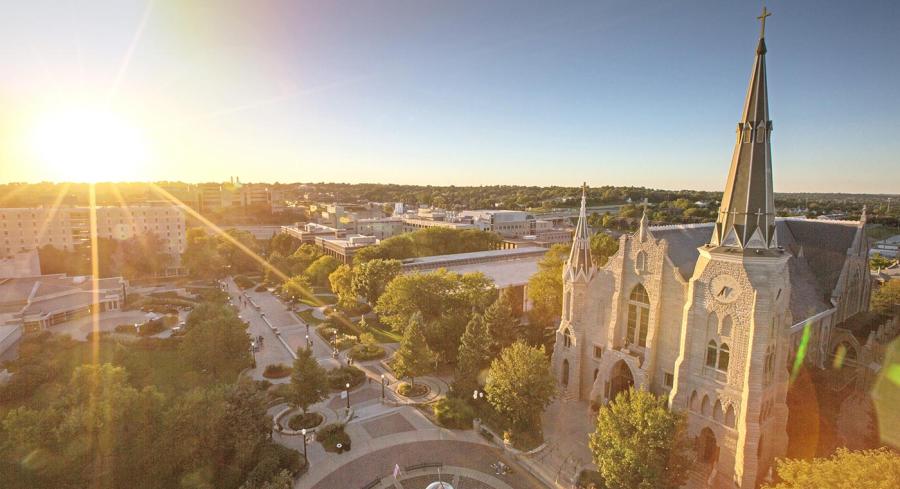

Alston, beginning in 1990 as an assistant professor of sculpture in the Department of Fine and Performing Arts at Creighton, is today a full professor and an accomplished sculptor whose seven-foot bronze of Cather was unveiled at Washington, DC’s National Statuary Hall June 7, making him the first African American sculptor to place a work there.

In 1970, however, for 12-year-old Littleton Alston, Statuary Hall was a magical, inspirational trip to another world, far removed from the poverty and danger of life where he lived. Here, free of charge, and open even to a poorly dressed neighborhood kid, was a landscape of glory, of heroes, of achievement and, like the Capitol dome itself where the Statue of Freedom watches over her domain, a sign of what might be.

“My family was not solid,” Alston recalls during a short break from the newest sculptures taking shape in his campus studio. “It was broken. We were seven children, but once divorce happened it was all very broken.”

His story was an emerging one for African American families during the years surrounding the civil rights triumphs of the 1960s. Absent fathers, struggling mothers, neighborhoods abandoned not just by white flight but also by educated Blacks for whom changing attitudes opened new vistas. Only the poorest remained. Whites, when they ventured into his neighborhood, were almost always there to shut off utilities for nonpayment or to deliver street talks about the dangers posed by various species of rats.

“Poverty was a very interesting thing,” Alston says. “If you are really poor, you don’t go around as a child thinking that you are poor. You really don’t. You just sort of rely on your friends and your community. You exist in an environment, and you relate to that environment the best you can. Poverty is an oppressive condition that can cause you either to shut down or to blossom.”

That he blossomed, Alston attributes to Gilbertha, who quietly and unobtrusively gathered the many sketches her son drew from a pile of old National Geographic magazines discarded by his elementary school librarian. Junior high was rough, he recalls, a place where real violence occurred, and where, inevitably, he was occasionally forced to defend himself with his fists. It was with a sinking feeling, then, that a day after a fight, he responded to an intercom message calling him to the principal’s office. But there, sitting in a chair, was his mother, cradling a makeshift portfolio of his drawings, composed of two pieces of cardboard held together by Scotch tape.

She wanted her boy out of there. She wanted him enrolled in the Duke Ellington School for the Arts, a recently founded public school whose glorious neoclassicist architecture thundered its mission of nurturing artistic genius. The middle school principal helped move the process along, including, Alston suspects, handing his mother the bus fare to the school, which was located in the tony and previously unexplored district of Georgetown.

Alston picks up the story: “We got there, and there was this big white building up on a hill,” he recalls. “Still the same, painted white. You showed them your portfolio, and then you sat at a round table where in the center was a still life with paper and containers of pencils. I was supposed to draw that still life. I turned to my mom, and I said, ‘I can do this. I’ve been drawing from National Geographic.’ So, I drew the still life and got in.

“I transferred into Duke Ellington because of my mother. She pulled it together. She always knew. She just knew.”

Alston came to Washington, DC, as a child, from Petersburg, Virginia, site of one of the great battles of the Civil War. His father, at this point still at home, had secured a job in the shipping and receiving department of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, a circumstance that led to Alston’s first encounter with the wonder of sculpture.

It’s a story he has told many times, how he accompanied his father one day to his workplace only to be struck by the towering Works Progress Administration-era sculptures of workers and horses that announced such agencies as the Federal Trade Commission where Michael Lantz’s “Man Controlling Trade” towered impressively. Fearful of showing up late for work, his father impatiently answered his son’s query about the origin of the statues with the odd assertion that they were made by convicts. From that moment on, Alston recalls, he knew he wanted to be a “convict,” whatever that was.

The seed was sown, and in the years thereafter Alston and one of his brothers could reliably be found pedaling bicycles cobbled together from old broken bike parts to the Capitol building, the beckoning tip of the dome just visible from his neighborhood. There they encountered not just art but the people of the world, drawn to the museums and artifacts of the Smithsonian Institution.

“I was astonished at what was there,” Alston says. “It was as though my bicycle was a magic carpet that had whisked me into some place where people were living different lives, speaking different languages, had different skin colors.

“It was the world. Here was this kid coming out of his rundown, dilapidated, rat-infested world and riding his bike to this other world, having previously supposed that his block was the world, that his four or five blocks were the universe.”

The years, of course, were slipping by, and the days of carefree meandering around Statuary Hall, utterly unaware that one day the work of his hands would be on display there, of splashing illegally in the Lincoln Memorial Reflecting Pool, of buying penny candy at the corner store, were numbered. He had lived through the wreckage of the riots after the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., and remembered well the flickering, threatening light cast by burning buildings, and the flooding water from firehoses trying to quell the conflagrations. He knew of food deserts before the term was coined, of neighborhood “stores” where the primary product was liquor, with a side of overpriced white bread.

But that world was receding. Ahead lie a scholarship to Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond where he earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in sculpture, and from there to the Maryland Institute College of Art’s Rinehart Graduate School of Sculpture in Baltimore where he earned a Master of Fine Arts and received the school’s top honor, the Rinehart Award.

In 1989, he was accepted to the artist residency program at Omaha’s Bemis Center of Contemporary Arts. A year later, he joined Creighton’s faculty where he now serves as full professor of sculpture after filling Omaha’s civic scene with striking images of Martin Luther King Jr., St. Ignatius of Loyola, baseball great Bob Gibson, ARTS’57, football great Gale Sayers, a jazz band tribute to North Omaha’s musical heritage and so many others. Then, in 2019, he won a nationwide contest to create the Cather statue.

Alston has, he says, just one great regret: His mother, whose advocacy planted the seed of his success, had long passed by the time leaders of the nation and the state of Nebraska gathered on June 7, 2023, to unveil his “Willa Cather” at Statuary Hall. How he wishes she could have been there.

But then …

His older sister did attend. Again, let Alston pick up the story:

“She sat beside me, my eldest sister, who used to change my diapers,” he says. “We were to go up and pull a rope to unveil Willa. Everybody’s up there. (House Minority Leader) Hakeem Jeffries is up there. The speaker of the house is up there, and all the dignitaries from the state of Nebraska. She leaned into me and said, ‘She’s here.’ I just about lost it, but I felt it.

“It was very real.”