Religious faith and its expression in sports

Poor old God. There stand the multitudes, their praying hands begging divine favor upon the soccer player about to take a game-winning penalty kick. Discordant voices, however — hands also joined in supplication — beg favor on the goalkeeper.

What’s the Creator to do? Like foxholes, there are no atheists in sports, not, at least, when everything’s at stake. Indeed, it has often been observed that in some places — New York City, perhaps, or Manchester, England — sport carries the flavor of religion, complete with cathedral-like stadiums and generational piety.

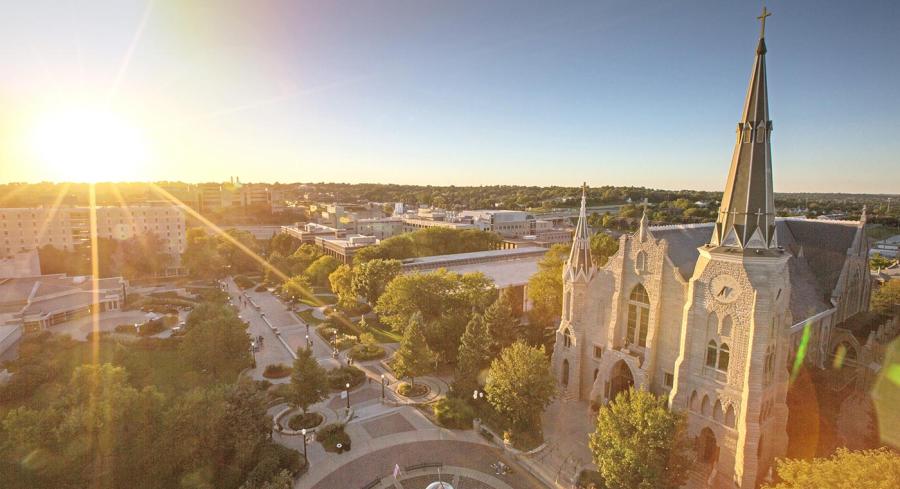

This relationship between the human experience of religious faith and its kindred expression in sports has been the subject of much thought at Creighton, especially in the work of College of Arts and Sciences faculty members Max Engel, PhD, associate professor in education and theology, and Jay Carney, PhD, associate professor of theology.

“As the Jesuits would say, you find God in all things, not only in explicitly religious activities but everywhere,” Carney says. “We have found that often the most profound experience students have of the transcendent, of moral formation, of community and relationship, have come not necessarily in a formal church setting but through a sports team.”

And, of course, less edifying elements too, such as cheating, betrayal, the full spectrum of human experience, the good and the bad.

“In some ways,” Engel says, “you might argue that sports teach valuable lessons, but the research says that you have to be really clear about what is being taught because sports unfortunately can tap into our basest tribalistic mentalities.

“Sports can act as a proxy for economic, social and cultural differences such as we see in Scotland, where the historical Protestant/Catholic divide has shaped the conflict between the Glasgow Rangers and Glasgow Celtic soccer teams.”

Religious Impulse, Passions Unleashed

The two Creighton professors are clearly on to something. Chess grandmasters do not run around celebrating checkmate. Stage actors do not pause the proceedings to punch the air after a well-delivered oration.

So, why does sport inspire such obeisances? What is the relationship between the religious impulse and the passions unleashed by sports?

Addressing these questions caused Engel and Carney last year to join forces with Matt Hoven, PhD, associate professor of sport and religion at the University of Alberta in Canada, to publish On the Eighth Day: A Catholic Theology of Sport. The book resulted in Engel being invited to a 2022 Vatican conference on inclusivity in sports. If that weren’t reward enough, he met briefly with Pope Francis, himself a sports enthusiast, who was given a copy of the book.

The conference cast light on the significance of sports to the human experience as understood by the Catholic Church. Titled “Sport for All: Cohesive, Accessible and Tailored to Each Person,” the conference encouraged participants to break down barriers to sports involvement for as wide a spectrum of people as possible. The conference identified longstanding issues of disability, gender and income as barriers, but also the development of what might be described as “sports cartels” in whose hands the business of sports is increasingly concentrated.

“Whether it’s the European Super League, or UCLA and USC joining the Big Ten, or the increasing expense and professionalization of youth sports with 10-year-olds going to tournaments in Florida and California and Las Vegas, the conference represented a prophetic voice calling us to recognize that sports are not to be commodified, that sports are for everyone to encounter, because in sports people encounter each other, themselves, and, ultimately, God,” Engel says.

The theology course (Sport and Spirituality) that he and Carney teach at Creighton follows that path.

“The course starts with the premise that most students are familiar with and enjoy sports, both participating and viewing,” Engel says.

“But students are rarely asked what sports have to do with their religious faith and spirituality, or how sports can contribute to or detract from cultivating a more just and equitable society. Key to this is our claim that sports serve as a distillation of human experience that includes hope, joy, suffering, relationships and disappointment.

“What do these experiences mean in sports? In life? And ultimately, what do these experiences mean when viewed through a theological lens?”

A Receptive Student Response

Students prove receptive to this line of inquiry, Engel says, because the reality of loss, suffering, disappointment and other foundational human emotions are much more present to them through the experience of sports than through a theology class.

“For many of them, sports have been central to their identity and sense of self, which offers yet another fruitful opportunity for reflection and personal, spiritual growth,” Engel says, all critical elements of a Jesuit education.

Interesting and novel as this line of inquiry may be, potential students should know that the course involves far more than watching and discussing ESPN highlights.

Vivian Relan, who is pursuing a degree in exercise science with a minor in dance and had never previously considered the relationship between sports and spirituality, described the course as “engaging.” Each class, she says, saw students assigned a text discussing how sports related to emotions like envy, as well as to coaching, ritual and superstition.

“After taking the course, I now think spirituality is meant to enhance the experience people have with sports,” Relan says. “Through playing and practicing, we have the ability to experience God’s grace and recognize His presence.

“Sometimes, it can be hard to think about this, as sports can become the main focus of our lives, but it’s important to remember that sports are not just about winning or losing.”

The course proved a useful moment of reflection, Relan says.

“While we all have different beliefs, we can all take a step back and realize that God is working through athletes to give them the power to do all they can do,” she says.

The proposition that sports and religion might reflect each other had also not occurred to Andrew Crane, a Creighton student studying biology.

“The idea of sports intersecting with the spiritual and religious experience never crossed my mind until taking this course,” he says. “We discussed and dissected a wide variety of topics and views in class and asked important questions about why and how we act as people, how we deal with different events and emotions like excitement, joy, fear, suffering, and, ultimately, renewal — all through the lens of athletics viewed through a spiritual, mainly Catholic, scope of life.”

For Julia Staniszewski, a Creighton student pursuing a management and international business degree at the Heider College of Business, the course touched a religious disposition that already guides her life.

“Though I am religious, I didn’t really think there was much to say about religion and spirituality in sports,” she says. “I couldn’t have been more wrong.”

“We spoke about different types of religious belief in sports, including directly praying to God, and even more spiritual takes where athletes sometimes mention feeling an aura from their sports. My main takeaway was that if you look at a problem or situation in sports, more likely than not, there will be a religious tie.”

The modern secular world does not lack people who mock religious devotion even as they devotedly follow the efforts of 11 grown men to transport an oval piece of inflated leather across a white line located 100 yards away. Is this sporting devotion, with its significant expenditure of personal wealth, investment of time, and endless debate and analysis, an expression of religious piety? In religious terms, can God use sports to touch the human soul in ways that saints and sages did in prior eras?

Pope Francis certainly thinks so.

Pope Francis: Sports Can Develop Holiness

In a 2018 letter to the Catholic Church’s Dicastery for Laity, Family and Life, marking publication of a church document titled “Giving the Best of Yourself: A Document on the Christian Perspective on Sport and the Human Person,” Francis says sports can develop holiness.

“This pursuit puts us on the path that, with the help of God’s grace, can lead us to the fullness of life that we call holiness,” he wrote. “Sport is a very rich source of values and virtues that help us to become better people.”

“Giving the Best of Yourself” develops that thought.

“The Church has been a sponsor of the beautiful in art, music and other areas of human activity throughout its history,” it says. “This is ultimately because beauty comes from God, and therefore its appreciation is built into us as his beloved creatures. Sport can offer us a chance to take part in beautiful moments, or to see these take place. In this way, sport has the potential to remind us that beauty is one of the ways we can encounter God.”

Religion, and the religious impulse, are foundational human characteristics, Carney says, and so students learn to recognize its presence, both in the current day and throughout history.

“During the spring semester, we often have our students watch the Super Bowl as a ritual model of what a sports liturgy looks like,” he says. “We look at the history of Christianity in sports and the shifting attitudes toward social justice and race and especially how sports either encourages humanization and justice or how it encourages greater injustice.

“Then we look at questions of ritual and prayer in sports, even at how the Christian story of life, death and resurrection is mirrored in the sports realm.”

Finally, Carney says, there is the future of sport and its role in shaping souls.

“Many of our students have interest in coaching and may already be volunteer coaches,” he says. “I have found that the classes we do on mentoring and coaching, where we use things like John Wooden’s Pyramid of Success as a sort of Christian affirmation of what moral coaching can be, can have a big impact on students.

“For many of them the super-competitive phase of their sports life is over, but a lot of them do see coaching in their future, and maybe families in their future, and I think for those students the idea that sports, morality and spirituality relate to each other is a critical insight.”